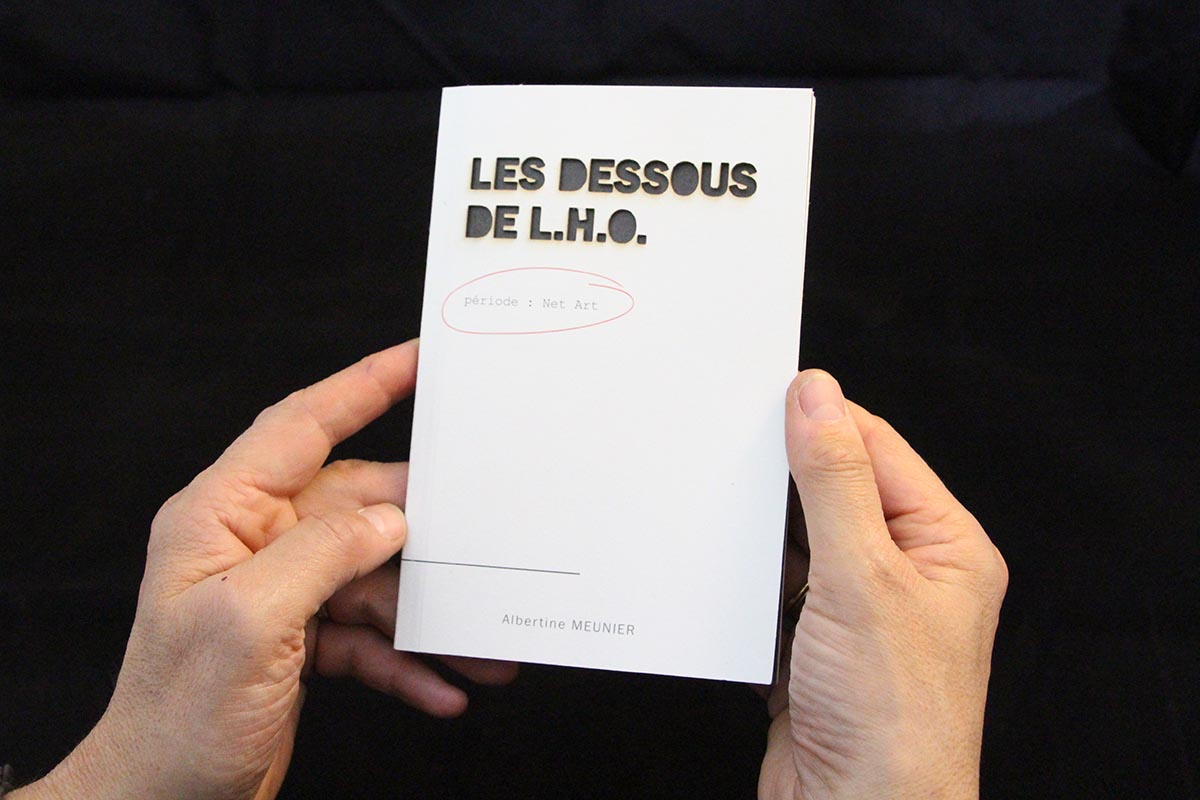

The Innards of L.H.O., the book

Ready Made Hack-performance since 2013, 27 July.

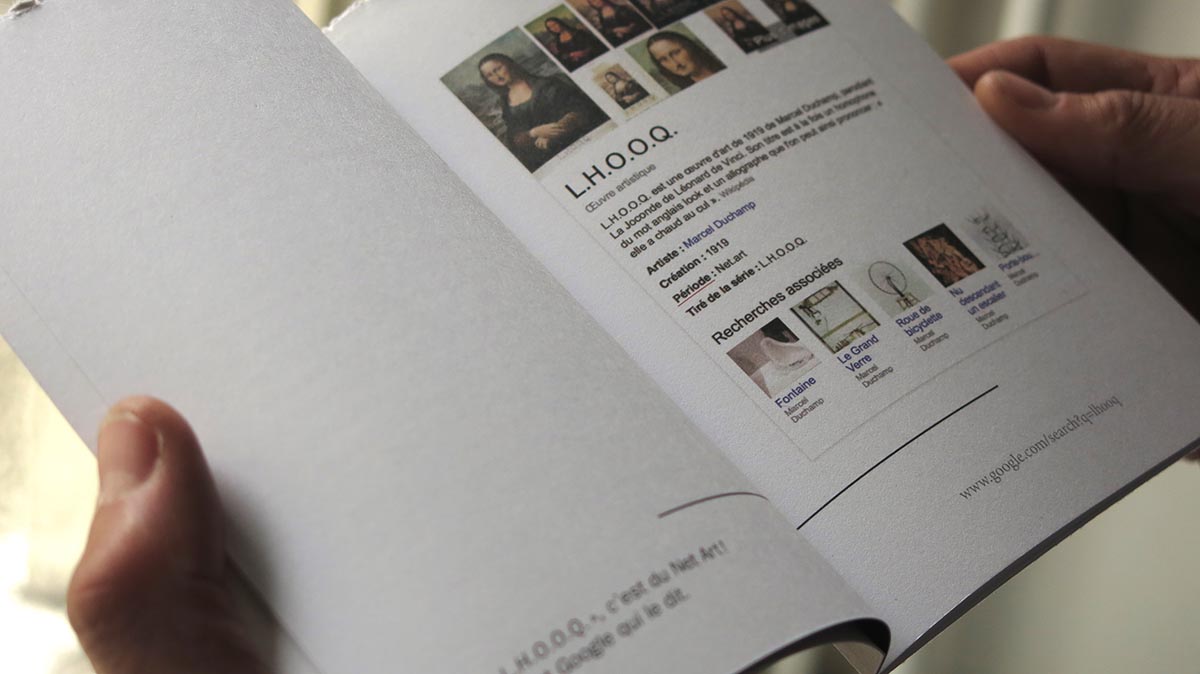

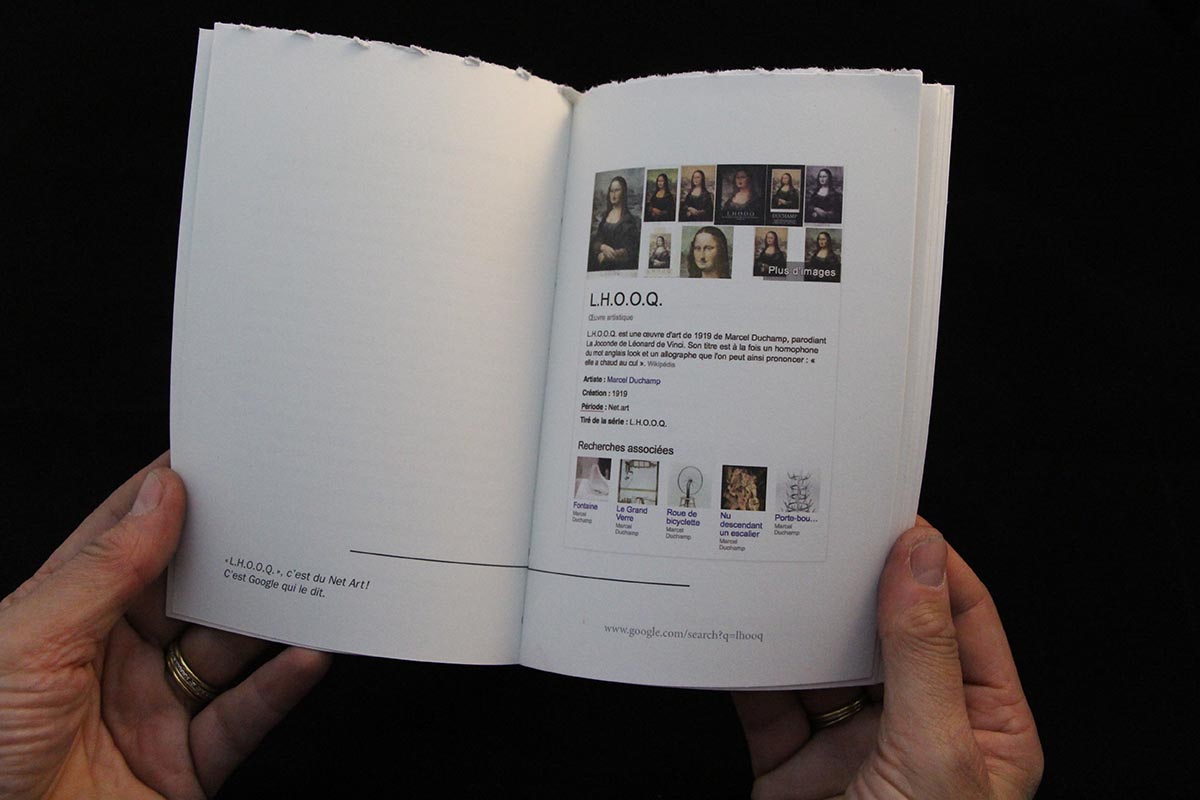

In the artwork The Innards of L.H.O., Albertine Meunier hijacks the little box that appears next to Google search results.

Through this artistic gesture, she decides that Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. dates to the period of Net Art, rather than Dada, as art history would describe it.

As such, she produces a sort of Readymade Hack on a piece that is itself a Readymade.

In fact, the first hack consisted of Marcel Duchamp adding a mustache to the Mona Lisa, transforming Leonardo da Vinci’s original artwork with a simple gesture. In turn, Albertine adds the Net Art label to Google’s search results for Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. by directly modifying the information in Google’s Knowledge Graph.

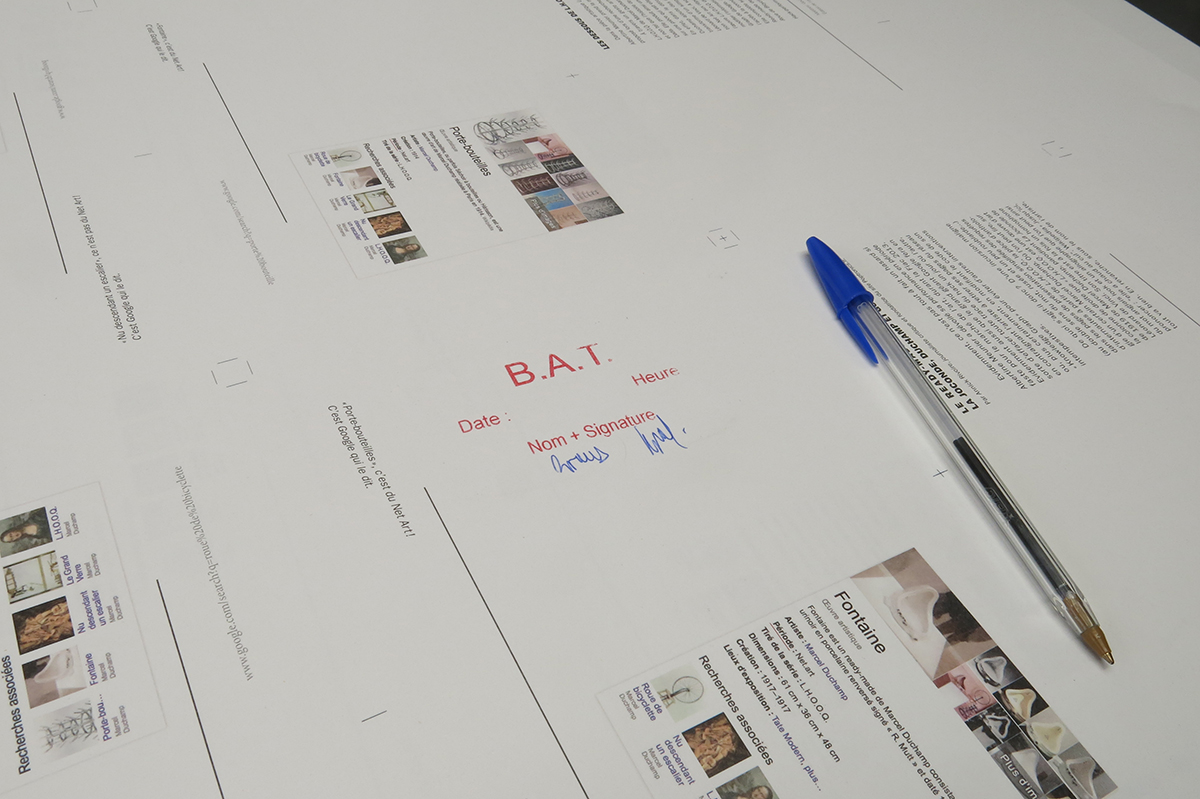

. Livrets . Edition in 404 samples

. Certified Tirages . L.H.O.O.Q c'est du Net Art! Edition en 3 exemplaires

You want to receive this book for free by postal mail, thanks to ask to albertine.meunier(at)gmail.com

The ready-made hack that gives the Mona Lisa, Duchamp and Google new clothes

By Annick Rivoire, journalist, critic and founder of Poptronics.fr website

Of course, it’s no coincidence that Albertine Meunier unveiled her performance at a peak time for the art market, during the FIAC contemporary art show 2013. And of course, Google will eventually get around to erasing all traces of the hack one of these days, by forcing the artist to remove her pages from the Internet, or more likely, by modifying the code to its Knowledge Graph to prevent other annoying interventions.

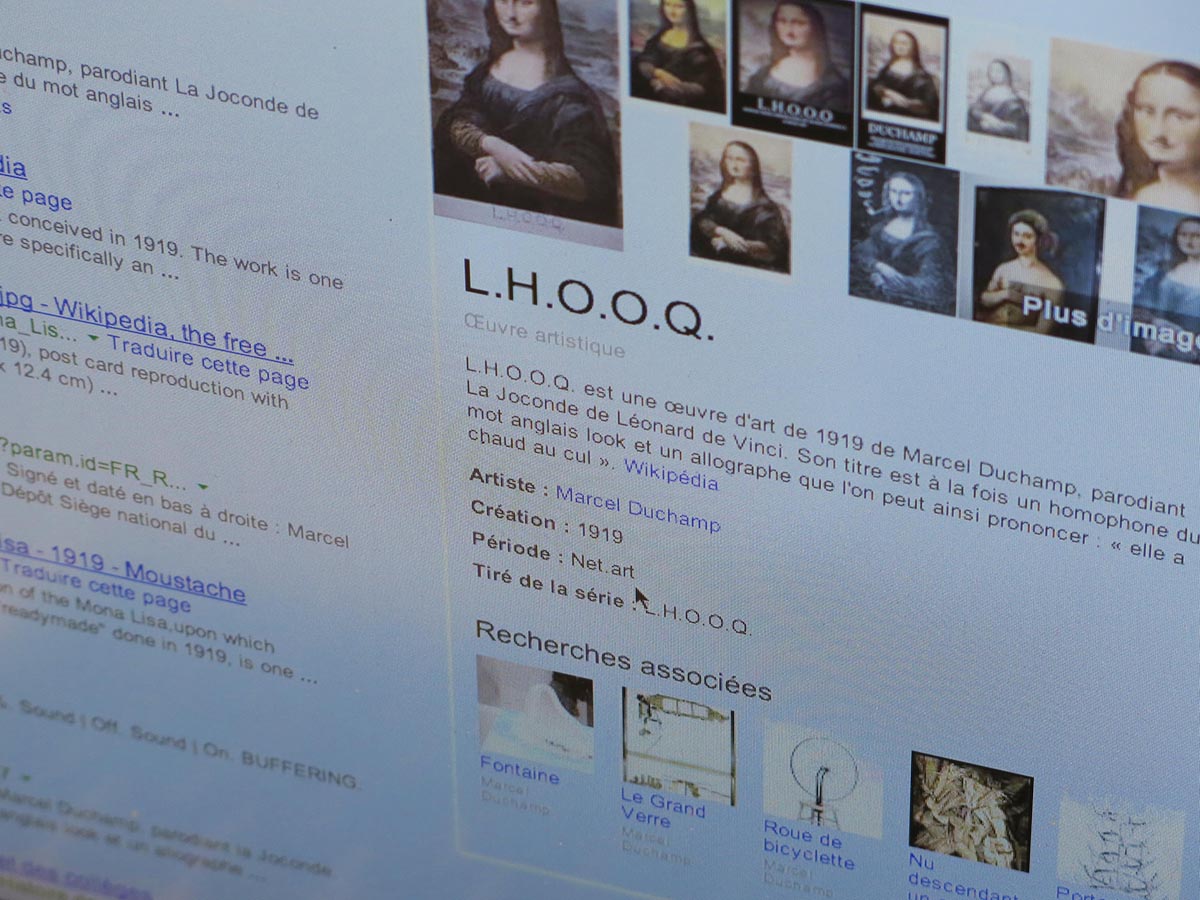

So what is it all about? A cleverly malicious incursion into the simplified presentation that accompanies Google search results for L.H.O.O.Q., undoubtedly Marcel Duchamp’s best known piece. The right column reads: “L.H.O.O.Q. is a work of art by Marcel Duchamp first conceived in 1919. The work is one of what Duchamp referred to as readymades, or more specifically an assisted ready-made. Wikipedia”. So far, so good. However, just below the date of the artwork, it is listed as belonging to the historical period of… “Net Art”. Obviously, Net Art did not exist in 1919!

Albertine Meunier’s online installation The Innards of L.H.O. falls directly in line with Marcel Duchamp’s work. But Albertine Meunier, as she revisits art history through Google’s filter, doesn’t stop there. She has attributed to a few of Marcel Duchamp’s pieces the same surreal category. Fountain (the infamous urinal), Bicycle Wheel, Bottle Rack are all categorized as Net Art, whereas Nude Descending a Staircase is qualified as “oil on canvas”.

Thus, the hack transcends the medium—it is no longer simply the image of a “blockbuster” artwork that is compromised, but its indexation in Google’s semantic insert. And the performance itself is double-edged. On the art side, attributing the Net Art label to Duchamp is loaded with symbolism and defends the movement by affirming its existence (one of the founders of Net Art, Vuk Cosic, announced its demise as early as 1996). On the Net side, The Innards of L.H.O. also represents the ongoing battle between Davids (artists) and Goliaths (online giants). A fringe of digital artists has been tackling the influence and norms imposed by online multinationals, as well as the mirages of certain technological discourses (Internet of Things, Cloud, etc). And they aren’t alone, as more and more “gurus” of cyberculture sound the alarm, such as Jaron Lanier, multi-inventor on the scale of the Internet (coiner of “virtual reality”), who criticized in Le Monde the false free-for-all that is currently robbing the digital revolution of all substance (1).

Amazon, Google, Apple… These past years, artists have tried to play down the leader of online shopping (Amazon Noir by Alessandro Ludovico, Paolo Cirio, Ubermorgen, 2007), proprietary online networks (Dead Drops by Aram Bartholl, 2010), the Cloud (Cloud Tweets by David Bowen, 2013) and P2P exchanges (The Pirate Cinema by Nicolas Maigret, 2013)…

It would be wrong to interpret these pieces as mere critical denunciation. Just as Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. openly mocked the genre of the Mona Lisa, while erasing in its own way a figure of art history (Leonardo da Vinci), they also seek to stir up debate, to question norms, especially when they are imposed without discussion. They are not anti-tech, just as Duchamp was not anti-art. They help open the eyes of those who massively use digital tools without ever questioning their limits. In this sense, they help citizens understand the challenges of new technologies.

Albertine Meunier, a thinly veiled pseudonym for a design engineer working in the telecom industry, has already attracted attention for her delicately poetic and critical pieces—Tweets that dance inside an old liquor bottle whenever an angel is mentioned on Twitter (Angelino, 2009), a sprightly network of cyber grannies baptized Hype(r)Olds (in collaboration with Julien Levesque, accomplice at la Tapisserie, a studio workshop where they fabricate alternative projects each year for FIAC at lafiac.com).

She has a talent for shining a spotlight on new media tools and their unlimited capacities, which redefine their applications. In The Innards of L.H.O., she unveils a tiny part of Google’s Knowledge Graph, which aims to convert its search engine into a knowledge engine. Google already dominates online search, thanks to its ranking algorithms. Since spring 2013, the Knowledge Graph appears to the right of its search results when you search the name of a person, the title of a film or artwork. “Discover answers to questions you never thought to ask, and explore the collections and lists of results,” announces the introduction page. “We’re building a massive graph of real-world things and their connections, to bring you more meaningful results.” Such is their proclaimed ambition.

Albertine Meunier points our attention to Google’s barely disguised hegemony, which, under pretense of technological progress (in short, the Semantic Web), offers to merge all the culture of the world into a knowledge machine. Except that this machine is not infallible, as Albertine aptly demonstrates, since she has been able to hack into the results with impunity since 27 July 2013...

As each passing day we become increasingly aware of the equivalency between being connected and being under surveillance, this little lesson comes as a public safety message!

1 . « Le Monde » 20 October 2013:

http://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2013/10/20/jaron-lanier-si-la-technologie-concentre-les-richesses-elle-va-devenir-l-ennemi-de-la-democratie_3499690_3234.html

It's Captain Kirk Net Art

By Etienne Gatti, art critic and exhibition curator.

Google, no longer content to be a simple search engine, now dreams of becoming a super computer—one that, like the iconic computer in Star Trek, understands our language and our thoughts and gives us answers rather than references related to our question. In short, a tool that finds—as Google says of its Knowledge Graph—“answers to questions you never thought to ask”.

This dream of organizing the knowledge of the world, source of discovery, irrigates all of universalist thought and is marvelously incarnated in projects of universal libraries, where the first experiences of serendipity took place. Google updates this ambition and puts it on steroids. It is no longer just about arranging images to work together and reveal the composition of myths, as in the panels of Aby Warburg (1), it is about articulating knowledge as a whole in order to create new knowledge. Above all, thanks to its Knowledge Graph, Google invites everybody to access it.

In order to achieve such a democratic entreprise, one can only imagine the power and complexity of an algorithm that only Google could author. In truth, it is just a simple meta database. All it took was for Albertine to hack this unique source of information and slip in the idea that Duchamp’s Ready-mades are Net Art to destabilize our finally fragile giant.

By becoming the exclusive provider of information and virtually our only access point to knowledge, Google is writing our History. In “The Collective Memory”, Maurice Halbwachs explains how each individual, each society reconstructs our past in such a way as to conform to the demands of the present (2). Individual memory does not exist. All we know of the past is what society, Google or our family tells us. In this set-up, Google, with its supposed algorithmic objectivity, incarnates and wishes to incarnate the legitimate source of knowledge. Google labels knowledge, including the fact that “L.H.O.O.Q. is Net Art”.

Through this double labelling—objective fact because Google and Net Art because art—The Innards of L.H.O., which went as far as to call upon a lawyer for certification, perpetually reflects the process of Duchampian designation. This wink at Marcel and appropriationist strategies is mildly amusing, while in this game of Russian dolls, we can’t be sure which of the two discourses—art or digital—includes the other.

The process depends on our recognition of the original work and its associated losses or approximations. The viewer takes pleasure in identifying an imitation and baptizes it as art by recognizing the intrinsic qualities of artwork status. Thus, Duchamp’s Ready-mades are indeed Net Art. This affirmation is perfectly accurate and irrefutable insofar as it refers only to itself.

In this game of artistic duping, the issue of hacking what is gradually becoming our source of knowledge remains. It’s a travesty of the truth that goes beyond artistic licence and points to both Google’s limits and our pragmatic and schematic approach (3).

Knowledge and power are more easily corruptible when they lie in the same hands. It is neither Babel nor its divine punishment. Here, corruption comes on the sly: delicate and delicious.

A few Netizens will notice, Google will notice, Google will modify Duchamp’s Net Art Ready-mades precariously and discreetly. To paraphrase Godard: It’s not just data, it’s just data. (4).

1. "Mnemosyne Atlas" is a project by Aby Warburg from 1921 until his death in 1929, which collects and categorizes by theme almost a thousand images from all periods. Warburg's work set the foundation for modern iconology and illustrates the concepts of hypertextuality and serendipity.

2. Maurice Halbwachs, « La mémoire collective », 1950. Quoted by Roland Recht in « L’Atlas Mnémosyne », 2012.

3. "All necessary reasoning without exception is diagrammatic. That is, we construct an icon of our hypothetical state of things and proceed to observe it. This observation leads us to suspect that something is true." Charles Sanders Peirce, "The 1903 Harvard Lectures on Pragmatism", 1903.

4. "It's not a just image, it's just an image." Jean-Luc Godard in "Wind from the East", 1970.

2014 – Albertine Meunier